Imagine you have a Rails monolith and want to add new functionality. Your options are to 1) continue adding to the monolith, or 2) create a new service. Which do you choose?

What if there’s a third option?

Background

Adding new functionality to a monolith is a lot like trying to add a new plant to an unruly garden. Do you put it in the same planter with all the other plants? Do you splurge on a new planter? How do you make sure it has enough room to grow? In Gusto’s case, that new plant was Time Tracking.

Time Tracking was a new feature we wanted to build and it seemed like a separate enough domain that it could be its own service. Before deciding, here are some guiding questions that we thought about:

- How tightly is the new functionality coupled to the existing code?

- What would be the touchpoints with the current monolith?

- Are the interactions real-time or asynchronous?

- Can we make use of callbacks or do we need to fetch data at runtime?

- What are the different parts of the monolith that interact with the new functionality? What would it look like if we were to separate those from each other?

The basic functionality of Time Tracking includes employees clocking in and out and editing their hours, managers reviewing these hours, and admins syncing these hours directly to payroll. At first glance, none of that seemed too coupled to the monolith; we counted just a handful of potential touchpoints with monolith resources. The interactions would be primarily real-time so data would need to be fetched synchronously. Given those factors, these were the options we considered:

Building inside the monolith

Pros

- There would be no setup costs and we could get started right away

- We wouldn’t need an API to access the models in the monolith from Time Tracking since everything is globally accessible

- We would have transactional guarantees

Cons

- The monolith would continue to get even more bloated

- If scaling became a concern, it’d be painful to try and ad hoc pull out Time Tracking into its own service

Creating a new service

Pros

- We would be starting fresh without all the baggage from our monolith--it’s a greenfield opportunity

- It would be easy to scale independently

- We’d be stopping the bleeding by not adding to the bloat of the monolith

Cons

- There would be high setup costs for something with an aggressive launch timeline

- Ongoing cost of maintaining a separate service with testing and deploys

- Getting the service boundary wrong would be very costly

I’ll admit that our first instinct was to go for the new service approach--microservices are popular and prescribed as the silver bullet to monoliths. However, microservices have their own set of challenges in testing and deploying and if we got the service boundary wrong, it’d be much more expensive to fix. Ultimately we went with a third option...

Building a rails engine

Pros

- It’s easier to get it up and running as it would live in the same repo but still provides some separation.

- The cost of getting the boundary wrong wouldn’t be as high as a separate service.

- It provides more flexibility; we could decide to split the engine out to be a separate service later, or not split it out, depending on how coupled the implementation is and future scalability needs.

Cons

- Data from the monolith could still be accessed anywhere from engine, and vice versa.

Building a rails engine seemed like a middle ground solution that gave us the flexibility to get the domain boundary wrong on the first iteration. Rather than worry about scaling issues from the start, we could keep the data in the same database until it needed to scale independently. However, having a rails engine doesn’t guarantee that the code would be decoupled since everything is still globally accessible. We needed to be mindful about drawing a clear boundary between Time Tracking and the rest of our codebase.

How we built it

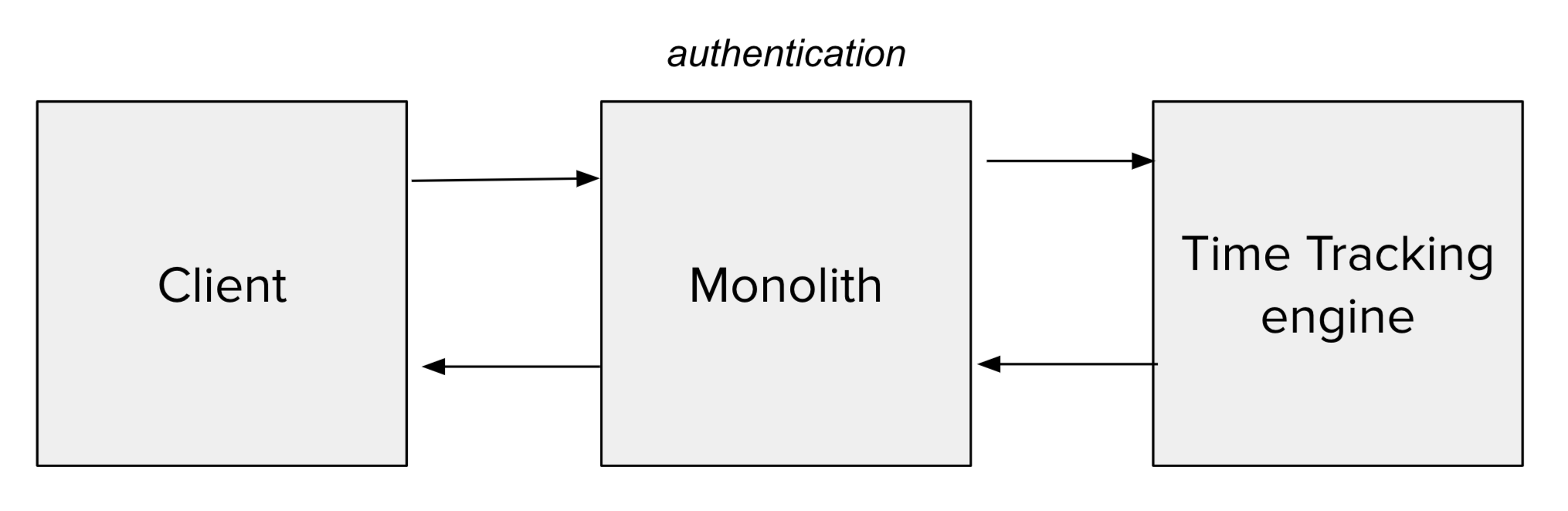

The main things we needed to figure out was how the frontend client would communicate with the engine, and how the engine would communicate back with the monolith. As we solved these, we were optimizing primarily for keeping Time Tracking as separate as possible from the monolith.

Service-client communication

Authentication still lives in the monolith, but we wanted authorization and all other business logic to live in the engine. What we decided was to use a reverse proxy where the monolith authenticates the user, and then forwards the request to the engine. This would mean that we have two controllers for what would normally be just one controller: one that lives in the monolith and authenticates, and one that lives in the engine to process the actual request and authorize.

Since the monolith and the engine both run in the same process, the request is not forwarded across a network boundary, but just calling the corresponding controller action. Let’s see what this looks like in code.

In the monolith, we have a proxy controller, which we’ve namespaced under TimeTrackingProxy:

app/controllers/time_tracking_proxy/trackers_controller.rb

module TimeTrackingProxy

class TrackersController < ApplicationController

before_action :authenticate_user!

def index

response = invoke_controller

render json: response

end

def controller_klass

TimeTracking::TrackersController

end

def invoke_controller

controller = controller_klass.new

controller.request = request

controller.response = response

controller_response = controller.process(params[:action].to_sym)

# Rails wraps the response in an array if there is content

controller_response.is_a?(Array) ? controller_response.first : controller_response

end

end

First the proxy authenticates the user, then we call invoke_controller which instantiates the Time Tracking controller from the engine, forwards the request, and processes the response back.

If we take a look at the controller defined in the Time Tracking engine:

time_tracking/app/controllers/time_tracking/trackers_controller.rb

module TimeTracking

class TrackersController < ApplicationController

def index

# business logic

respond_with @trackers

end

end

end

It looks like a typical controller, but without the authentication. The benefit of this is that if we pull Time Tracking out to be its own application, we would only need to change the proxy controllers and how they interface with Time Tracking. Similarly if authentication were a separate engine or service, we would also only need to change the proxy controllers. We also wanted to make sure that the proxy layer doesn’t contain any business logic and should only be forwarding requests.

Service-service communication

Although everything is globally accessible inside the engine, we wanted to create a clear API between the engine and the monolith. In order to draw that explicit boundary, we serialize and deserialize messages passed between the two. By only passing around serialized objects, we reduce the temptation for Time Tracking to make additional database queries or reach into private data with ActiveRecord models, and also be limited to the contract defined by the monolith’s API.

We define these services in the monolith and inject them as dependencies into the engine. We followed the configuration specified in the Ruby on Rails guide but instead of injecting ActiveRecord classes, we inject service classes that have a defined interface. This lends itself better to Time Tracking being a separate application, where we would only need to change the configuration of the services it depends on.

Testing

All our tests live together inside the monolith, which means that the monolith is still being loaded when we run tests. When testing Time Tracking, we stub out all API calls made to the monolith. Currently this isn’t enforced anywhere but just something the team practices. We also have integration tests to verify that the communication between Time Tracking and the monolith are working in order.

How is it holding up?

What’s been working really well for us is having the clear API boundary and making sure we aren’t passing rich objects across that boundary. It helps ensure we only pass the information we need and don’t accidentally reach for more. Having the code separated into an engine rather than living in the monolith has also made it easier to navigate the code and onboard new teammates onto the domain.

Some things that may not hold up as well if we were to truly pull the engine out to a separate service is the amount of data fetches Time Tracking makes from the monolith. It isn’t an issue now since this is all in-process, but across a network boundary it could cause some timeout problems. It’s a great reminder of continuing to be mindful about the domain boundary so that Time Tracking only knows what it needs to know.

What would we change?

While we were very mindful from the beginning about keeping Time Tracking separate, we could have done more to help enforce this. Having the tests run outside of the monolith from the get-go would have enforced that the engine isn’t accidentally reaching into the monolith since we’d be able to test the engine in isolation. Most of the communication is also synchronous request-response patterns when we could’ve leaned more heavily on publish-subscribe patterns to help separate concerns better.

Rails engines alone do not provide much separation other than having the code live in a separate directory, but encapsulating the domains by only exposing what’s necessary in addition to the code separation has been a valuable first step towards a modular monolith.

Some other great reads on creating a modular monolith:

https://medium.com/@dan_manges/the-modular-monolith-rails-architecture-fb1023826fc4

https://engineering.shopify.com/blogs/engineering/deconstructing-monolith-designing-software-maximizes-developer-productivity